Skating Out of the Binary

Why this matters

Figure skating has not kept up with sport's evolving relationship to the gender binary, even going so far as to specifically delineate gender for pairs athletes. But at the grassroots and professional levels, competitors are working to progress the sport toward a more inclusive and open environment.

Figure skating is behind the times, and my pairs partner, Anna Kellar, and I are on a mission to bust open its gender rules. We are two white queer adult skaters. I’m a cisgender woman and Anna is trans nonbinary. We met in group lessons at the ice rink in Portland, Maine, and found we had a lot in common, including a social-justice vision for figure skating and beyond. We first teamed up 2019 to perform a number for a local LGBTQIA2+ benefit. Now we want to take our U.S. Figure Skating (USFS) qualifying test and compete.

To do so, we need rule changes. Interestingly, for at least a decade, USFS has departed from the International Skating Union (ISU) in declining to specify the gender make-up of a pairs team. Rule 7020 begins: “Pair skating is the skating of two persons in unison . . .” Stop there, and we’re in. We might also draw hope from the inclusion of nonbinary skaters among those spotlighted in USFS’s amped-up promotion of equity and inclusion: Eliot Halverson, Andrew Sass, who wrote a middle-grade novel on the topic, and Timothy LeDuc, a pairs champion with partner Ashley Cain-Gribble.

Yet Rule 7020 also states that “only pairs of the same composition (lady and man, two ladies or two men) may compete against each other.” Meanwhile, Rule 7221 stipulates that qualifying tests required for pairs competition must be skated by a woman and a man, and the official definitions of tricks specific to pairs go so far as to identify a man’s role and a woman’s role.

What’s up with the massive contradiction between the open-gender “two persons” and the extremely restrictive details? I suspect that the open-gender component has exactly one purpose, which is a laudable one: to allow USFS to endorse competitions like the Gay Games that have “same-sex” pairs events. In contrast, the ISU, which regulates international competition, threatened until 2018 to punish skaters for participating.

To open up Pairs altogether would require dismantling numerous beliefs and practices. Primary among those is the assumption that men - or more precisely people judged to have bodily characteristics traditionally gendered male - always have competitive advantage. Far from being specific to figure skating, this false belief underpins numerous harms. It makes routine gender segregation in sport, contributes to understating other sources of advantage (such as money for training), and abets anti-trans policies as well as other forms of racialized gender policing. Witness allegations that Serena Williams, Caster Semenya, and other Brown and Black athletes, particularly from the Global South, are not sufficiently female, or, possibly, not dressed appropriately. By this contested standard, a pairs team with two men would threaten to overwhelm all others.

Second, as I and others have discussed elsewhere, figure skating, a sport dominated by white European balletic ideals—and in which people competed as “men” or “ladies” until June 30th of this year—has long suffered from the interconnected problems of homophobia, white supremacy and defensiveness against the popular derision of figure skating as too feminine and too artistic to count as a sport. This toxic brew affects who skates, how they skate, and what wins points. It contributes to pressure on queer skaters to remain closeted and to rigid, if tweaked, norms concerning appearance. My own expression of femininity, I’ve discovered, often goes unrecognized as such, despite skirts and nail polish, partly because I wear black skates, violating a gender convention so strong that switching skate color is often a key source of joy and legibility for trans skaters. Coaches, parents, judges, skaters, club officials and sometimes rink staff contribute to norm maintenance.

LeDuc, who strives with his partner Ashley Cain-Gribble to portray gender equity, points out that pairs skating usually elevates “hetero-cisnormativity,” representing a “fragile girl” and a “strong man” in stories of romance or rescue. That doubling down on binary gender contrast, which is spoofed in the movie Blades of Glory, takes work to pull off in a sport that prizes making hard stunts look effortless and simultaneously requires strength of all participants. Both Anna and I are at the gym building muscles we need to participate in lifting.

But the core tricks of pairs skating facilitate that binary scenario, as Anna and I are learning more about through training. Before starting pairs training, we competed separately at the USFS “Adult Bronze” level, which requires single-revolution jumps and one-position spins. Now we’ve been working on throw jumps, coordinated footwork, a pivot figure (prequel to a death spiral!), and lifts, which, as Anna puts it, requires an additional sport’s-worth of training. Our heights map us onto a conventional cisgender Male/Female pairing, even if our identities don’t, meaning Anna has the traditionally male roles of lifter and thrower. We can’t really take turns, though at first we tried. Neill Shelton, one of our coaches, thoughtfully refers to “the taller person’s” role rather than “the man’s,” keeping a focus on the actual issue. Taller simply does better lifting or throwing shorter, for leverage and other reasons. Even less difficult features have height considerations, like whose arm goes around whose waist in the standard Kilian dance position.

In thinking about what’s baked into pairs skating, keep in mind that no sport has natural core components. Sports develop in relation to numerous entangled values. At higher levels, they encode who should represent the nation. Who might be basketball’s elite if playing in wheelchairs was the default versus the parasport variation? These values also determine participation. Who might be Adult figure skaters without a sedimented history of white supremacy that makes some people (including Anna and me) more likely able to pay for lessons (and innumerable other costs) while also less likely to encounter the subtle or explicit racist obstructions that Joel Savary, founder of Diversify Ice, documents in Why Black And Brown Kids Don’t Skate.

Still, pairs skating has core moves that, we have to admit, are thrilling to do. So we are working on other ways to subvert invited narratives, including in related movement genres like ballet. Happily, we have a lot of models to inspire us, including many queerly configured pairs who have performed or competed outside of the USFS/ISU events. For example, genderqueer lesbian choreographer Katy Pyle, who had been pushed out of ballet as a teenager for being “too big (and) too muscular,” founded Ballez in 2011, a ballet company that moves the subversion of “ballet’s coded gendered gestures” from the margin to the spotlight, with performances about unionizing garment workers, AIDS activism, and a reworking of The Firebird into a story of “trans self-actualization within an explosive community of radical queers.” Genderfluid dancer Ashton Edwards is part of a movement, attracting even some mainstream companies, to rethink whether only women can dance on pointe.

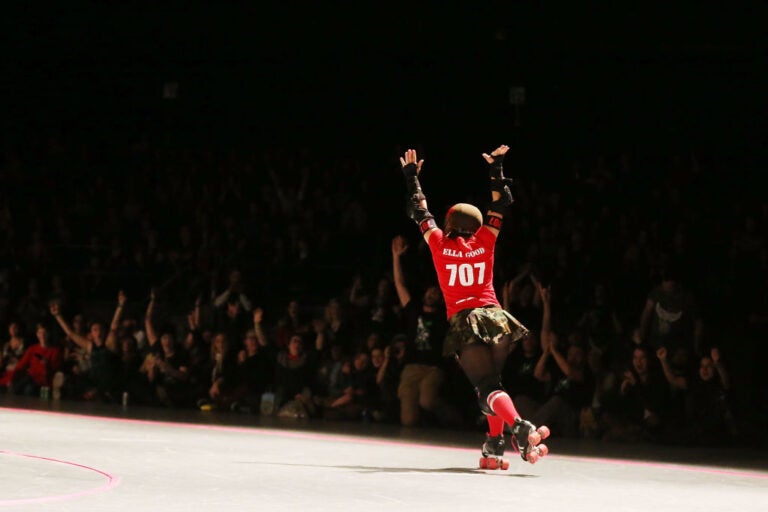

Figure skating, Halversom and LeDuc emphasize, as with LGBTQIA2+ history more generally, builds on the insufficiently acknowledged liberation work of queer and gender nonconforming Brown and Black people, such as Rohene Ward (skating here in 2016 to music by genderqueer Prince) or Latinx out gay skater Rudy Galindo, whose 1996 National Championship performance to "Swan Lake" and 1998 performanceto a Village People medley were pathbreaking in refusing the codes of skating gender. Others like Surya Bonaly, Midori Ito, Debi Thomas, and I would argue, Tonya Harding were pathbreaking in refusing to get out of skating when their visible athleticism, spectacular achievements, and racial and/or class distance from aristocratic whiteness disqualified them from ideal femininity.

We also look for inspiration and ideas to our own division of adult skating. Amy Entwistle, for instance, has been a rock star of non-traditional gender presentation at Adult Nationals, including in her 2010 winning skate to "Bolero." As she explained last year, “Skating transcends the polarity of gender for me. . . . ‘I typically feel feminine on the ice, though elements of my music, choreography and costume choices might be considered masculine by skating standards.’”

In addition, American Ice Theatre, Ice Dance International, and Ice Theatre of London are among skating companies presenting and promoting skating outside the confines of traditional competition, and many queerly configured pairs have performed or competed outside of the USFS/ISU events. Check out Joel Dear and Christian Erwin. Or long-time Gay Games competitors Alan Lessik and Johnny Manzon-Santos and Birgit Aust and Bettina Keil. The latter pair is particularly instructive for us because, like them and unlike most pairs, we have the extra athletic and choreographic challenge of rotating our jumps in opposite directions from each other.

We love what’s possible outside the system. We also want into the system, which should expand to include all gender (or agender) configurations, including cis-hetero pairings of non-normative size.

Social-justice and anti-oppression work includes expanding access to pleasure and joy. As activists, athletes, friends and skating partners, we are happy to join the growing movement to transform our sport, skating our way out of the binary.

Erica Rand’s writing on sports includes Red Nails, Black Skates and The Small Book of Hip Checks. This piece benefited from thinking with her students at Bates College in Queer and Trans Sports Studies.