Elladj Baldé Wants to Redefine What It Means to Be a Figure Skater

Why this matters

Growing up in figure skating, Elladj Baldé didn’t see himself reflected in the sport, and he felt like he couldn’t fully be himself and fit in. Now, he’s trying to make the sport more inclusive, so more skaters can feel at home in it.

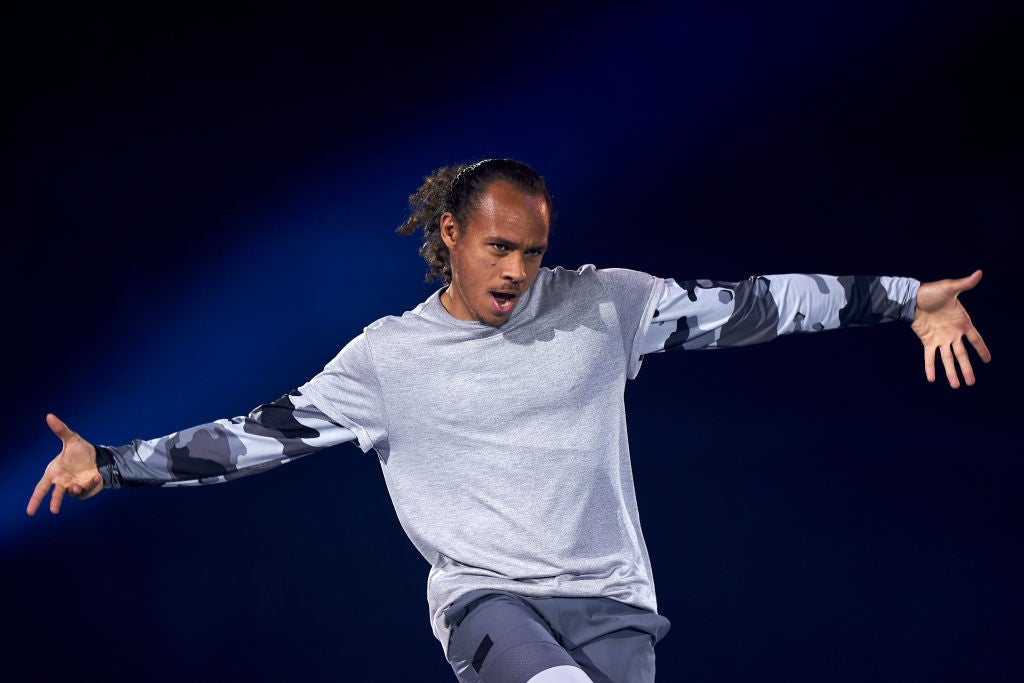

On a frozen lake nestled among snow-covered mountains, a man wearing a Chicago Bulls jacket is skating, his movements carefully synchronized with soothing piano music. His skates carve white curves in the dark ice. In another video, set to a Drake song, he launches himself into the air, does a backflip, lands skillfully, and keeps going. This is Elladj Baldé, a biracial Canadian figure skater who’s working to make skating more accessible and inclusive to more people.

Baldé challenges boundaries in figure skating – including stereotypes about race and masculinity and the types of music and choreography skaters use. He retired from competition and from the Canadian national team in 2018. He won the Canadian junior title in 2008.

The videos Baldé shares on TikTok and Instagram show him skating and dancing to all kinds of music, from James Brown to Justin Bieber to Labrinth, expertly choreographed by his wife, the dancer and choreographer Michelle Dawley. He has developed quite the following online and hopes his impact can keep growing.

“I want to change the culture of figure skating,” Baldé says. “I want to change the way people perceive it so that we can allow boys to be in a sport and be themselves and know that they can be part of it in a way that feels right for them – and then also create a space where Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) can be themselves as well and be celebrated for that.”

This month, Baldé is at the Winter Olympics in Beijing, reporting on figure skating for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, where his impact will reach beyond skating broadcasts.

Related: Can the Beijing Winter Olympics Jump-Start Women’s Pro Hockey in North America?

Canadian figure skater Vanessa James will also be in Beijing, competing in the pairs event, and she is a global brand ambassador for the Figure Skating Diversity & Inclusion Alliance. She has spoken out about the importance of making the sport more inclusive and, along with Baldé, has served as a mentor in the alliance’s Big Skater Little Skater program. This program pairs BIPOC mentor skaters with young BIPOC skaters.

“We want to be part of that journey with them and help them, whether it’s emotionally, psychologically, to be there for them before competition when they’re stressed, but also try to find resources, to find skates, blades, costumes, and financial resources,” Baldé says.

As the child of a Russian mother and Guinean father, Baldé felt out of place in the mostly White and wealthy world of figure skating. “The sport has been used to seeing a certain type of skater on the ice, which is usually the White European skater. It’s molded around that identity,” he says.

Decades ago, Black skaters weren’t even allowed to compete. For example, in the U.S. in the 1930s, figure skater Mabel Fairbanks was barred from competing because she was Black. She later coached several high-profile skaters and became the first African American to be inducted into the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame. A 2018 U.S. Figure Skating survey of fans showed that 73 percent are Caucasian, 18 percent are Asian, 3 percent are Hispanic, 2 percent are African American, and 1 percent are Native American.

“A lot of skaters from the BIPOC community that join the sport of figure skating, the first issue you see is that you don’t see yourself at the top, you don’t see yourself competing in the Olympics, you don’t see yourself competing and winning medals on the national level,” Baldé says.

The sport is also expensive, putting it out of reach for many kids. “For a lot of kids growing up in underserved communities, joining a figure skating club, with the cost of skates and ice rental and coaching and traveling, is not possible,” Baldé says. “My parents struggled immensely, trying to keep us in the sport, and if it wasn’t for coaches that essentially taught me for free for most of my life, I wouldn’t be here now.”

These barriers compelled Baldé to create an organization that would make the sport more inclusive and accessible. He and Dawley founded the Skate Global Foundation and partnered with construction company EllisDon to build outdoor rinks in underserved communities across Canada. The first opened in Calgary, Alberta, in December. People can use the rinks and borrow skates for free. “They might fall in love with the sport, especially if the environment feels like home – feels welcoming to them,” Baldé says.

The Figure Skating Diversity & Inclusion Alliance aims to foster a more diverse and inclusive figure skating environment around the world, and it has made a difference. “It’s created a community of Black, Indigenous, and people of color that can feel safe to share their experiences and be together,” he says.

Skating and Masculinity

Baldé says he was always bullied for participating in a so-called girls’ sport. “The first time I experienced and felt shame for being a figure skater was at the age of nine,” he says. “It was really sad, because I was so excited. I won a competition. And then I went to see one of my neighbors, and I was still wearing my figure skating costume and my medal. And I was so excited to show my medal because it was my first gold medal.” The neighbor’s response was: “What the hell are you wearing? You’re wearing a costume. Girls wear these things.”

Baldé’s pride in what he’d achieved doing what he loved turned to shame. That began a process of feeling like he needed to prove that he was man enough, he says. “It was a long journey for me to redefine what it is to be a man because, in our society, you’re supposed to be stoic, non-emotional, you deal with your problems on your own, and you don’t talk about your problems, you don’t talk about your fears. And those are all things that, actually, as a human being, are extremely important to live a healthy emotional and psychological life.”

Related: American Sports Perpetuate ‘A Certain Type Of Manhood’ - Here’s Why It Persists

He hopes to dispel those perceptions by sharing his version of skating with others. “A lot of boys leave the sport of figure skating because of being teased and made fun of,” he says. “And it’s sad, because so many boys are passionate about skating but will never allow themselves to continue in the sport because of what society has told them figure skating is.”

Artistry and Authenticity

Baldé is broadening the definition of what figure skating is. His videos don’t look like typical figure skating routines, especially when they include backflips, which aren’t allowed in Olympic competition, or when they’re set to rap music.

“Being biracial – my mom being White, my dad being Black – I grew up watching Russian figure skating, and there was a part of me that obviously is connected to my Russian culture,” he says, so he started following that path at a young age. Later, he says, “I started to realize that I had so many interests – in terms of the type of music I listened to, the way I liked to dance, the way I liked to dress – that were completely different from what I was doing and from what I felt like I was allowed to do on the ice.”

He struggled with that tension. “When I started winning competitions, I started getting rewarded for fitting that mold. And so that reinforced this idea that there’s no way for me to truly be who I want to be on the ice and be successful: I had to choose one or the other,” he says. But then, when he was a teenager, he saw a Black skater at a local competition. “That completely changed my perspective on what’s possible for me, because he was truly being authentic to himself, and he was technically good. He was different on the ice, and that kind of spoke to me in a way that I’d never been spoken to before.”

That encounter is when Baldé’s perspective started to shift. By his last few years of competing, he says, “I was authentically competing with music I wanted to skate to, wearing what I wanted to wear,” while staying within the rules for certain jumps and other technical elements. “Once I did that, once I felt that type of authenticity, I’d never competed so well. The audience, every time I performed, were up on their feet,” he says.

“There was so much raw energy around it, because I was operating from that space. And I think that’s what we’re missing from figure skating right now,” Baldé says. “It’s so technically focused that everyone looks the same.” It’s not that striving to master the technical elements is bad. Doing so has elevated the sport, he says.

However, he explains, “someone who isn’t a figure skating fan doesn’t know the difference between a quad toe and quad flip. What speaks to them will be the overall feeling that they felt, but that’s kind of lost in the sport right now. Because we’re not being rewarded for being artists. We’re being rewarded for being technicians.” A better balance between the two would make the sport more inclusive, he says.

Mental Health and Body Image

Figure skating is an especially subjective sport, Baldé says. “You’re judged on your appearance. You’re judged on what you’re presenting. You’re constantly judged, and you’re given a score,” he says. “That can have a really, really, really negative impact on someone’s mental health when they’re constantly looking for this approval from judges.”

Mental health is one of the Skate Global Foundation’s three pillars (the other two are equity, diversity, and inclusion; and climate change). “We’re trying to kind of change the way skaters approach figure skating,” Baldé says. “In turn, we see a lot of high-level athletes actually perform better because they’re more focused on themselves, and they’re creating this unique moment when they’re performing. And people really vibe with that.”

Skaters constantly being judged and comparing themselves to others may also lead to unhealthy behavior. Eating disorders and body image issues are rampant in figure skating.

Many skaters have toxic relationships with food, Baldé says, including himself. For him, it’s less about body image than performance, he explains. “My weight has to be so specific in order for me to perform at a certain level that there were times where I was obsessed with my weight.”

Climate Change and Ice

Baldé started skating on wild ice – frozen lakes – last year. “My connection to ice formed by Mother Nature is an experience that I’ve never had before. And it’s deeply grounding,” he says. He wants future generations to be able to experience that, But he knows that climate change has caused certain lakes to freeze later and later, or not to freeze at all anymore—and that some communities depend on the lakes freezing. So the Skate Global Foundation is working to highlight the importance of taking action on climate change.

Of the messages Baldé gets from people who see his videos, he says the ones he appreciates most are the ones that say: “I don’t watch figure skating, or I don’t like figure skating, necessarily, but what you do speaks to me.”

“When I get these kinds of messages,” he says, “it reassures me that what I’m doing – and the intention I’m operating from – is the right one if I want to help change this idea people have of figure skating.”

If Baldé didn’t experience the things he did in the sport, “I probably wouldn’t be skating the way that I’m skating now,” he says. “It’s thanks to these experiences that I’ve been able to transform that and use it as a gift to share with others, because that’s my story. That’s my message.”

He adds, “That is what I want every skater to strive toward, really – using those experiences, whether positive or negative, to create their own story and then share that.”