Study shows HBCU teams penalized more than others

Why this matters

Creating an even playing field - and eliminating bias - makes the athletic experience rewarding for everyone.

Same series. Same umpiring crew.

Different strike zones.

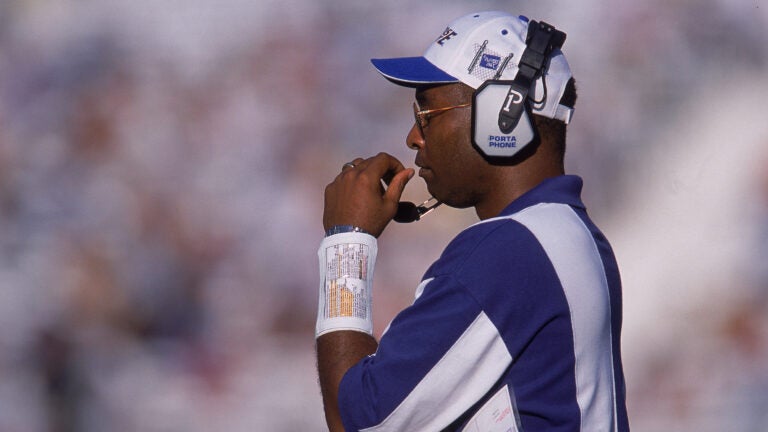

“There are Division I coaches, and this is in the Power 5, they complain from the first pitch to the last pitch,” noted Kerrick Jackson, the baseball coach at Southern University, a historically black university in Baton Rouge, La. “No matter what it is, it’s always something.

“And they go on and on, and there are umpires that will take that. Then, late in the game, it works in their favor, and they might get that call. Whereas if we coaches at historically black colleges and universities do that, there’s no shot.

“There’s a comment for every pitch, every strike, every call. And as an opposing coach, I’m like, ‘Shut up.’ And the umpires just take it.”

He’s not certain if it’s a race issue — after all, predominantly white institutions, or PWIs, have a significant number of African-Americans on their rosters as well. But officiating bias against collegiate athletes and coaches from HBCUs — tangible or perceived — is a real thing, Jackson said. A status thing.

Same series. Same umpiring crew.

Different vibe.

“The head of our officiating group was (at our offseason meetings), and the one thing I told him is there was a blatant disrespect with regards to how those (umpires) come over at you over the course of a game,” said Jackson, who took the head job at Southern late in the summer of 2017 after stints as an assistant at Missouri, Nicholls State, Jefferson (Mo.) College, Fairfield, Emporia State and Coffeyville (Kan.) Community College. Southern isn’t a small fry — the program has won or shared 26 Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC) titles.

In his first campaign with the Jaguars, Jackson noted at least five specific incidents “where the umps were flat-out wrong … It wasn’t a judgment call. It wasn’t a bang-bang play. It was wrong from a mechanical standpoint, and it was wrong from a justification standpoint.”

To wit: On one play at first base this past spring, Jackson recalled seeing a first baseman’s foot leave the bag, and clearly.

“And I say to the home plate umpire, ‘What do you have?’” the coach recounted. “He said, ‘I’ve got the foot on the bag and the ball in the glove.’

“There may be some people that go out, ‘It’s the SWAC, let me just do this and collect my money.’ I think it’s more subconscious, that there’s a heightened sense of awareness when I’m in the SEC or Conference USA. Now that’s not working hard — I just think it’s a subconscious mentality that allows things to take place in foul calls and that kind of stuff and how coaches are treated.” - Southern University baseball coach Kerrick Jackson

“I said, ‘There’s no way you can (tell it’s in the glove). From 90 feet away, you can’t hear that the ball hit the glove. And he says to me, ‘That’s what I’ve got.’ At that point, there’s not much I can say. You’re flat-out wrong. And because you’re flat-out wrong, I can’t argue ignorance.”

Later that same weekend, in similar circumstances, the home plate umpire deferred to his counterpart at first base, who declared that he was 100 percent sure the first baseman’s foot was off the bag this time, giving the runner the base.

“I go to the home plate umpire and he tells me, ‘(The ump at first) was 100 percent sure and I wasn’t,’” Jackson sighed. “So it’s little things like that. If we were in the SEC, there’s no way that happens. Again, instant replay factors into that.

“And we had some other calls like that, where it was blatant — they were in the wrong place, (made) a bad judgment call or because they didn’t know the rules or they didn’t know what they were doing. That is very prevalent at this level, where we don’t get the same level of attention to detail. I don’t want to attack it and say (it’s) professionalism, but they do have a shorter fuse. And, again, to me that’s disrespect.”

According to a recent study, such disrespect might be systemic, too. Andrew Dix, a professor of communication studies at Middle Tennessee State, released a study that underscored how women’s basketball teams from HBCUs receive more fouls called against them than teams from PWIs, based on data from 2008 through 2017. It was the second HBCU-related officiating analysis Dix has conducted in the last three years. In a 2017 piece published in the International Journal of Science Culture and Sport, Dix showcased data on 10 college football seasons — 2006-2015 — that revealed HBCU football programs were penalized more frequently than peer schools at the Football Championship Subdivision level.

In Dix’s study, HBCU women’s hoops teams accounted for eight of the top 15 most-penalized Division I programs over that 10-season stretch and held each of the top 5 spots. Overall, 23 HBCU schools were found to have been whistled for an average of 1.5 more fouls per contest than the 310 predominantly white institutions.

“And the crazy part about it, crazy as this may sound, I almost think it’s subconscious,” said Jackson, who, as a student-athlete, walked in both worlds, having played at an HBCU (Bethune-Cookman) and at a PWI (Nebraska). “I don’t think it’s a conscious deal.

“There may be some people that go out, ‘It’s the SWAC, let me just do this and collect my money.’ I think it’s more subconscious, that there’s a heightened sense of awareness when I’m in the SEC or Conference USA. Now that’s not working hard — I just think it’s a subconscious mentality that allows things to take place in foul calls and that kind of stuff and how coaches are treated.”

Lack of funding could impact perception

Perceptions are like habits — the older they are, the tougher they are to break. The four lowest-scoring APR Division I men’s basketball programs during the 2016-17 school year, and five of the bottom 10, hailed from HBCUs.

“I could almost feel when we played HBCUs (in college) that there was a (different) experience and even just characterization of these athletes,” recalled Akilah Carter-Francique, who, like Jackson, has represented PWIs (as a hurdler and long-jumper at the University of Houston) and HBCUs (as a professor at Prairie View A&M) both athletically and academically.

“A lot of those sentiments of what (Dix) found are not necessarily shocking to me. And in the research I’ve done at HBCUs and understanding how they’re perceived in general, and even experienced, and we as African-Americans … some look down on them as well, even those who have not attended (HBCUs), so I could see how that tradition of bias could definitely come into play, to the referees that may be working or officiating those games with those young women.

“Even this day, the way we are at the present time… I’ve attended events in Prairie View A&M gear and the looks of individuals in those games — I’m like, if I’m getting it in the stands with my children, it would be interesting how they were receiving it with their engagement in the (arenas) with those referees.”

Because it’s not just a status thing; it’s a money thing, too. Of the 230 Division I schools tracked over the 2016-17 school year by USA Today, seven of the bottom 10 schools in terms of athletic department revenue hailed from either the HBCU-led SWAC or MEAC conferences (Prairie View ranked 150th; Southern checked in at No. 188).

“The salaries from Alabama’s football coaching staff dwarf a large number of HBCUs’ entire operating budgets,” noted Joseph Cooper, an assistant professor at the University of Connecticut’s Neag School of Education and the founder of Collective Uplift, an organization designed to empower, educate and inspire students of all racial and ethnic backgrounds.

“When you put that in context, it’s like, ‘Hold on, now … you’ve got to account for that.’ Think about that. If you had a team that has a $1.2 million recruiting budget, and they’re playing a team that has a $50,000 recruiting budget, you can imagine the way that game may play out. There’s going to be some different outcomes, and I’m talking about officiating (outcomes) compared to if they had the exact same resources. But I think if you’re going to make that (conclusion), I think you’ve got to account for the resource (gap) and how that’s engaged to systemic racism.”

Cooper said Dix’s research underscores a bias of resources more than, say, race. Power 5 basketball programs, for example, seldom engage mid-majors in true road games. For Power 5 football programs, HBCUs and programs of similar scope have traditionally traveled to the larger institution’s stadium for “guaranteed” contests that promise a sizeable check and, usually, lopsided outcomes.

“Another question would be which officials are officiating those games,” Cooper said. “You’d have to look at each official individually and as a staff. If there’s a trend — that when these officials are working with these opponents, then this many penalties are called. It’s not a far-fetched thing to say that officials, just like any other person in our society, perhaps have implicit bias.”

Although the financial trickle-down effect can be seen in facilities, staff, support system and depth of quality talent, Dix contends it is not just a money thing — it’s a style thing, too. And another perception, one that the HBCUs play a more physical, a more raw, a more undisciplined style on the football field or on the court than their PWI peers.

“In all likelihood, there are probably a number of different reasons an increased number of personal fouls are being called against HBCU women's college basketball teams relative to PWI women's college basketball teams — and likely a number of different reasons referees are calling more penalties against HBCU college football teams relative to PWI college football teams from the 2006 through the 2015 season,” Dix wrote via email.

“Specifically, it could be argued that HBCU women's college basketball teams play a more aggressive style than PWI women's college basketball teams. It could be argued that more personal fouls have been called against HBCU women's college basketball programs because they have fewer resources than PWI women's college basketball teams. It could be argued penalties that are born out of the APR results lead to more personal fouls being called against HBCU women’s college basketball teams. It also could be argued that elements of racism are still embedded in various elements of the American sports fabric. The same arguments are applicable to the college football study. Regardless of the interpretation, the uncovered data speaks for itself.”

Finding the right way to point out the discrepancies

And what it says isn’t always … kind.

“I’m not saying it’s right, the way they’ve been treated,” Carter-Francique said. “But for these young women to be able to process all that’s happened to them, that it’s vitally important that they understand from whence they came and how different situations are experienced in certain places. And that, being a student-athlete, you’re an ambassador for the university, you wear a certain hat.”

To that end, Carter-Francique in 2015 co-founded Francique Sport and Education Consulting, a mentoring group focused on education, research and diversity. It’s purpose is to put the best of what we preach into actual practice.

“You’re going out to represent your institution, so my goal as a coach, my goal as an administrator (is) to engage them in that conversation, so they would be able to understand that from a fuller perspective and not take it personally,” the Prairie View A&M professor explained. “So they could understand the historical context … For some, and depending on how that interaction is, it can escalate some feelings. And you don’t want to get into situations there where you could get a technical foul.”

Dix’s advice? If you’ve got a beef, don’t suppress it. Air it at the appropriate times, through the appropriate channels. Don’t presume the worst. But, by the same token, don’t settle for anything other than someone’s absolute best.

“I would make the argument that it all starts with HBCU athletic directors,” Dix said. “They are sufficiently empowered to bring light to this narrative. Their voice is the loudest. Their voice is less likely to be muted than that of players or coaches.

“Creating a dialogue is the best thing an HBCU player, coach or athletic director can do in an effort to bring about meaningful change. That sounds a bit cliched to say, yet the referee penalty discrepancy between PWIs and HBCUs has been occurring for years. Little has been said about this phenomenon.

“Creating a dialogue is the best thing an HBCU player, coach or athletic director can do in an effort to bring about meaningful change. That sounds a bit cliched to say, yet the referee penalty discrepancy between PWIs and HBCUs has been occurring for years." - Middle Tennessee State University professor of communications studies Andrew Dix

“That noted, it is important to keep in mind that referees are humans. Sometimes they will make mistakes, just like anyone else. And just like anyone else, they are prone to playing favorites and/or sometimes allowing personal biases to influence their decision-making in certain sports-related contexts. Being a referee is a tough job. As we move forward with new technologies, I think this line of research offers evidence that utilizing more computer-based technologies to make discretionary calls in the field of play being used — such as PITCHf/x — would benefit certain sports and specific plays in the field. In the meantime, fostering a dialogue on referees calling more fouls against HBCU teams relative to PWI basketball teams is a good starting point for creating awareness that will better inform players, coaches and sports consumers.”

Speaking of pitches, Dix’s next project is a manuscript on HBCU college baseball for a book chapter that’s slated to publish in 2019.

“The preliminary evidence has revealed that more walks per nine innings are being called, when the pitcher on the mound represents an HBCU relative to when the pitcher on the mound represents a PWI,” he noted.

All of which steers him back into Jackson’s orbit, and to a sport that, according to the NCAA, comprised players who were 73.8 percent white and 9.7 percent black among Division I programs in 2017-18. The ratio gap is even more pronounced when it comes to head coaches — 89.6 percent Caucasian and 4.4 percent African American. This past spring, 13 of the 298 baseball coaches at the major-college level were black.

“I think it’s twofold,” Jackson said. “On our end, from a coaches’ perspective, it’s about people being able to maintain that level of professionalism. And carrying that with us at all times can disarm them from having that thought process. If they act in a way that our reaction is what they expect it to, then that validates their {thoughts). If we fly off the handle after every wrong call, they can say, ‘See, I told you.’

“And then it’s about keeping officials accountable by filling out evaluations. If it’s just one coach, and he’s always negative on everybody, then they’ll say, ‘Well, OK, we can discount him.’ But if it’s everybody, that’s different.”

Sean Keeler has written for several media outlets, including FOX Sports, The Guardian, American Sports Network, and Cox Media’s Land of 10 and SEC Country verticals. You can follow him on Twitter @SeanKeeler